Reflections on my Tutorial with Jonathan Kearney

The Feedback

My first tutorial with Jonathan was very surprising and inspiring. He was very positive about the writing I’ve been posting on my blog. I posted it on there because I want to bring it into my practice but I’m not sure how. I was fascinated by his shared interest in the nursing model I’d referenced and his feedback about what I’d written. This is hard to process. I work in isolation in the Scottish Highlands, juggling motherhood chaos while trying to build a fine art practice. Validation like this feels both essential and almost impossible to absorb. But I’m trying.

Nursing Models and Art Practice

I’ve been bringing Prochaska & DiClemente’s transtheoretical model of change into my reflections, a framework from nursing that understands something art theory often forgets: behaviour change is circular, not linear. Relapse is expected. You move within the cycle multiple times before behavior change properly take root.

The stages move like this: pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, (potential relapse), back to contemplation.

The light bulb moment for me was this: pre-contemplation is when we don’t know what we don’t know. Contemplation is the moment of awareness, when the issue becomes visible. These moments need capturing or they disappear in an instant.

Jonathan mentioned he’s been reading nursing research too. This matters because nursing models, particularly those grounded in communication theory (Prof. Anne Marie Rice’s work), understand that communication underpins everything, in nursing and in art practice. How we communicate with ourselves, our materials, our audience. She would often say during nursing lectures that ‘trained monkeys could do most nursing procedures’ but emphasised that the communication skills needed by the nurse to carry this skills out in a professional and compassionate manner were foundational to clinical excellence.

The Problem: Stuck in Contemplation

I told Jonathan I’m procrastinating from resolution. I feel like I’m constantly swirling with ideas, trying things out, never drawing a line in the sand and saying “this is finished.”

Why? I think it’s about confidence.

Without finished work, I miss the opportunity to reflect on it, learn from it, move forward. I’m stuck in an eternal preparation phase, the foggy internal state where nothing becomes resolved work. I know what I’m avoiding. I’m avoiding the vulnerability of presenting something as complete, of allowing it to be assessed, of risking failure.

Capture as Central Concept

This word has positive and negative connotations. Photography: capturing light, moment, time. Encaustic: capturing graphite within wax, trapping pigment. Writing: capturing words on a page so they don’t escape forever. Archive: capturing light bulb moments before they’re lost to the ebb and flow of contemplation. But capture has inherent tension: to cage versus to protect. To frame versus to trap. To preserve versus to control.

My scanner work captures botanical materials at a precise moment in their lifespan. The scanner bed is a frame, flat, controlled, rectangular. But what I place on it refuses stillness. The materials are dying, transforming, leaving marks, petals, spores & curling away from the harsh scanner light. I’m documenting impermanence, but the act of documentation itself becomes a kind of preservation. Maybe I’m trying to protect these specimens from their inevitable route back into soil by making time stand still for a second?

When I’m Making My Best Work

Jonathan asked me: “When you’re making your best work, what’s it like?”

I told him: The maker disappears. I’m no longer the doer. I have this inbuilt knowing, I know where to put my hands, where to move the pigment. Words or thoughts are simply not neccessary. There’s a state I reach where language and intellectual thought falls away and something else takes over. My hands know. My body knows. I’m responding to something I can’t articulate.

I didn’t have the vocabulary to explain what that state is.

Not yet.

Learning Tacit Knowledge at Art College

At Edinburgh College of Art, I studied in what was then called the Tapestry Department (it’s since been renamed Intermedia). Many of my tutors were weavers. They said it was about a “weaving of ideas,” but really, the department had a deep focus on tactility and materials. That’s what I loved about it.

We learned about tacit knowledge, though I didn’t fully understand it at the time. Weavers have this fundamental knowledge of touch that’s easy to overlook. They know when the loom is too tight or too loose. They know the feeling of the thread. It’s muscle memory, stored somewhere unconsciously.

Michael Polanyi, who first described the theory of tacit knowledge, wrote: “We can know more than we can tell.” He was talking about a unique kind of knowledge that can’t be put into words. It’s that’s passed from human to human through observation, imitation, & practice. A language embodied by human hands.

This is the knowledge my tutors carried. And it’s the knowledge I’ve been seeking ever since.

Sometimes I think about printing my photography, getting it professionally done, efficient and clean. But I can’t bear to. I want to make it myself with my hands. I want the tactile engagement, the feel of paper, the smell of chemicals or wax, the physical labour of pressing botanicals, of moving pigment. I can’t explain why exactly, but if I send it away to be printed, something essential would be lost. The knowing that happens through making would disappear. I would lose touch with my work.

Polanyi also said: “The tool, when in the hands of someone who is competent, becomes invisible to them, or rather, becomes like an extension of their body.”

That’s what I’m learning. The scanner bed, the encaustic iron, the graphite, the paper, they’re becoming extensions of my hands. I’m learning to work by feel, not just by sight.

A Conversation with a Silversmith

Yesterday I was talking with my sister, not my twin, but my other sister who lives on our farm in a little cabin. She’s a silversmith and jeweller. Self-taught. She built her practice by going to markets in London when she had no money, buying incredibly well-made handmade jewellery from all over the world, and learning by fixing it. By taking it apart. By understanding how strong, practical, beautiful jewellery is fabricated. Her business began with her finding an abandoned frying pan in a skip and her first pieces were soldered in it. Now she takes a bag of scrap silver and turns it into rings that look machine-made on first inspection. But they’re not. They’re handcrafted with absolute love and meticulous attention. She can work silver from melting it down to polishing the finished piece. She has an intimate relationship with her material.

She told me something extraordinary: “Sometimes I don’t even look down at what I’m doing. I do it by feel. It’s tactile.”

I was blown away. You reach this level of mastery over your materials where looking becomes secondary. You’re using other senses. Touch. Temperature. Weight. The surface and physicality and three-dimensional structure of the piece. Tacit knowledge. Muscle memory. Knowledge that doesn’t exist consciously until you bring it to the forefront to articulate it to someone.

She said: “To an onlooker, it might look like I’m forcing my materials, hammering them, sawing them. But actually I’m responding to them. It’s much more subtle than forcing a design onto materials. It’s a tight balance. An interaction. I’m responding to what state the silver is in at that moment.”

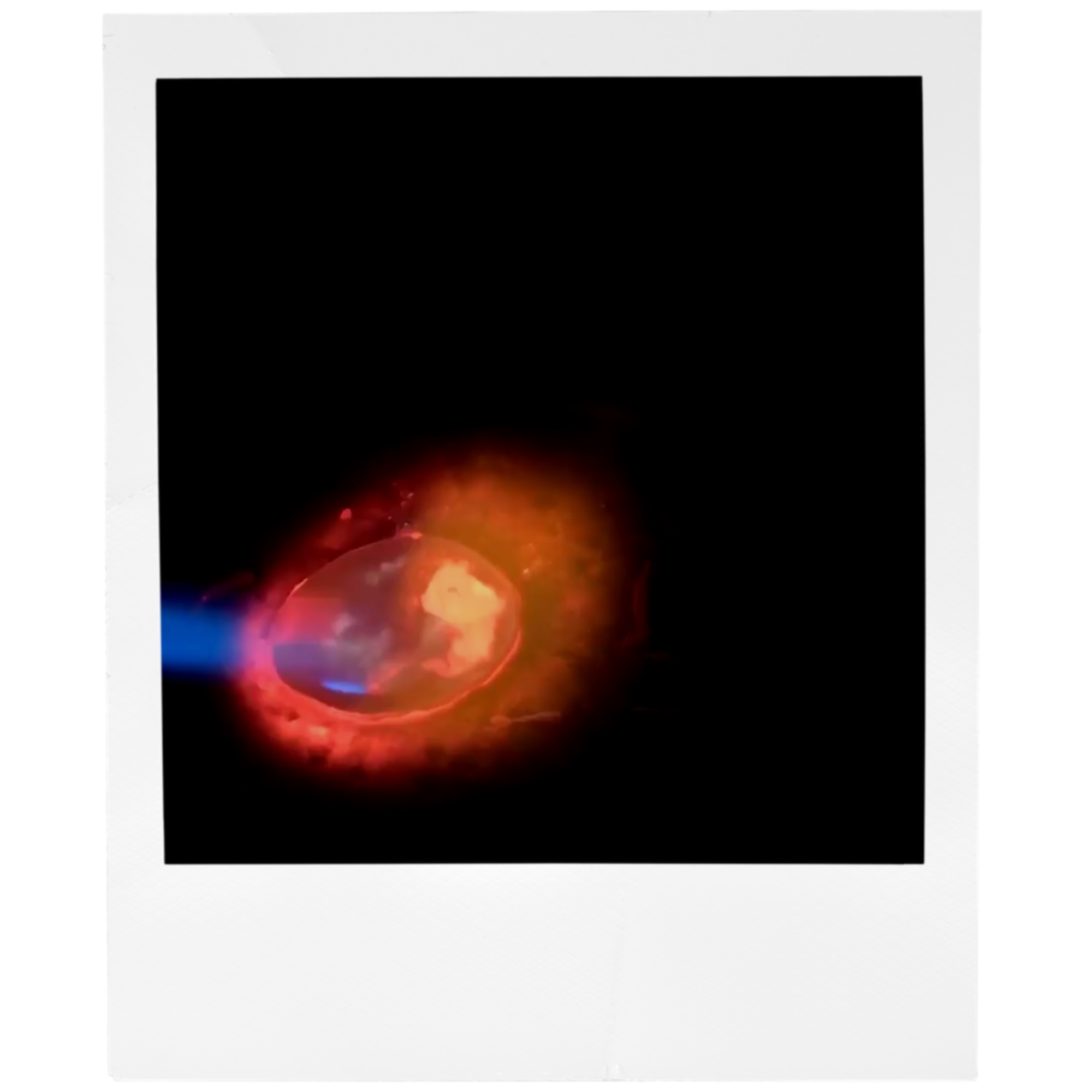

Soldering is the perfect example. Has the solder liquefied to the perfect temperature? Not a tiny bit hotter, not a bit cooler. If it’s too hot, everything melts and the piece is destroyed. If it’s not hot enough, the join won’t be strong. But there’s a sweet spot where it’s perfect.

She’s learned this, not intellectually, not through traditional instruction, but through tacit knowledge. The feel of when something’s right. This knowledge is stored somewhere unconsciously. And to access it, she said, you need to be in a state where you’re more removed from your conscious mind.

This is exactly what I described to Jonathan.

The state where the maker disappears. Where my hands know where to move the pigment. Where words become hindrance.

My sister doesn’t consider herself an artist. She says she’s a maker. But we come from the same place. We both understand that making is collaboration with materials, not force. or control.

Do Not Go Plumb

My sister trained for years in historic building conservation, working with an incredibly inspiring Alison Davies. One of the most important rules she learned: Do not overfinish things. Do not make them too straight.

If you “go plumb”, make something perfectly vertical, perfectly straight, it will look wrong.

Old Scottish buildings embraced so-called imperfection. They had curves, variations, idiosyncrasies. And they looked right in the landscape. They felt right. Buildings that are too straight don’t feel right. There’s something unsettling about geometric perfection imposed on organic contexts.

My sister brought this rule into her silversmithing. She doesn’t overfinish. She leaves traces of the hand. Evidence of process. Natural variation.

I said to her: “It’s like when you look at the horizon. You rarely see a completely straight line.”

Even at the beach, looking at the horizon where water meets sky, there’s always variation. A dolphin jumping. Waves moving. Birds flying. Boats bobbing. Light changing. The horizon is in a constant state of flux and movement.

My GP once told me to look at the horizon for five minutes a day. Apparently it helps with mood, with mental health. Of course it does. It reminds us of context. Of the vastness and expansiveness that exists around us. Our place within that is actually very small, not in a self-deprecating way, but in a relational way.

We don’t exist in our heads – this simple fact is easy to forget. We exist in the world. We’re ruled by seasons, by light, by nature. Our eyes are the only part of our precious central nervous system that is exposed to the outside world. This says a lot about how important light is to us on a physiological level. Light entering our bodies through our eyes affects us profoundly, even when we’re not always conscious of it.

During lockdown, we were starved of horizon lines. Starved of context. Trapped within walls and their straight edges.

The Beehive Frame

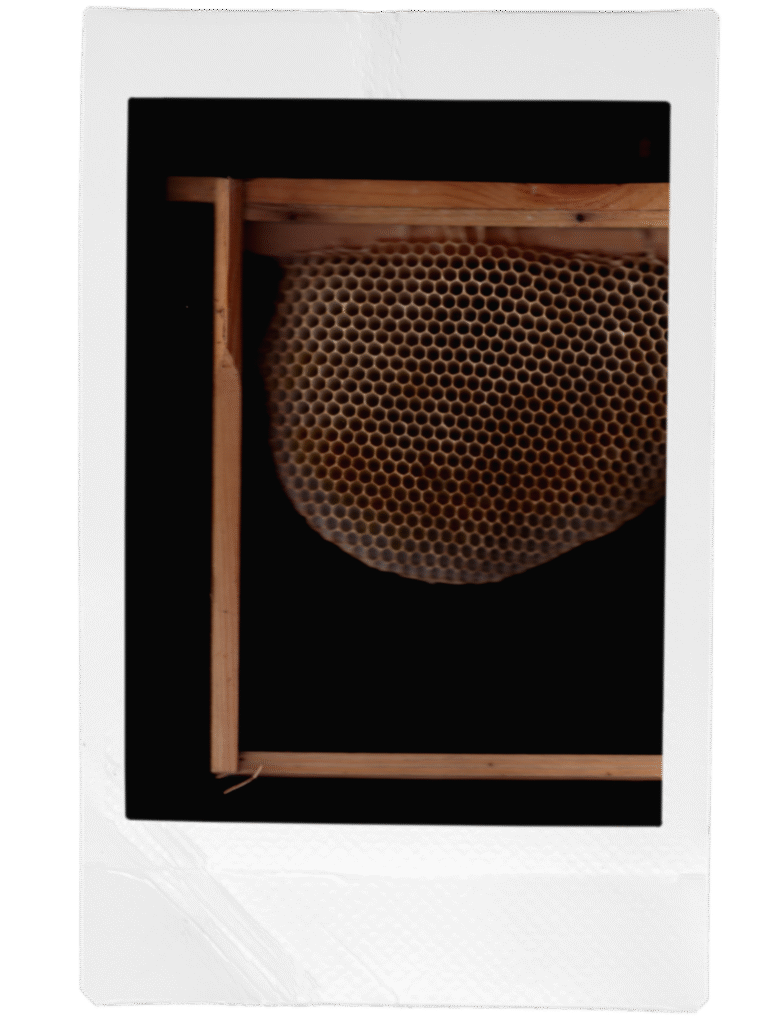

Today I was editing photos of beehive frames on my iPad. Wooden frames, human-made, rectangular, with corners. Designed for efficiency. For control.

Inside these frames, the bees make honeycomb. It undulates. It’s structural, yes, the basic hexagonal pattern, but it’s nuanced, beautiful, strong. There are so-called “mistakes” in this structure, but they’re just natural variation. The bees accept it. They work with it.

We humans like to create straight lines because it’s more efficient. But bees are incredibly efficient too, they just manage it without straight lines. They have a freedom in their making and often overrule the straight lines imposed on them by their beekeeping overlords.

The frame can’t contain the organic reality inside it. The bees overflow out of the hive frames and respond to the entire cavity of the hive. They see the potential in the empty space outside the frames whereas beekeepers see it as their territory.

I was struck by this because Jonathan had mentioned my writing about moving to Musselburgh, how I described the landscape shift from the rural Highlands (curves) to the city (corners). Corners rather than curves. It’s a theme that keeps surfacing in my work.

Here I am, editing a photo of a human-made rectangular frame, and inside it is this bee-made structure that refuses geometric perfection. That collaboration between human intention and natural process. The tension between control and variation. Between capture and freedom. Moving outside of the box.

What This Means for My Practice

I work with frames, literal and metaphorical.

The scanner bed is a frame. Flat. Rectangular. Controlled. A technology designed to capture documents, to fix information, to reproduce exactly.

But I’m not using it to fix information. I’m using it to document transformation. I place botanical materials on the scanner bed, dying, decaying, bleeding colour, curling, refusing stillness. The scanner captures a moment, yes. But the materials are already changing. By the time the scan is complete, they’re different.

I’m working within the frame, but I’m documenting what can’t be contained by the frame.

Like the bees.

Like my sister’s silver, looks like force, is actually far more subtle than that.

Like historic Scottish buildings, imperfect, curved, right in the landscape.

My practice is about collaboration with materials, not force. About responding rather than imposing. About the state my sister described, where you’re removed from your conscious mind, where tacit knowledge takes over, where your hands know before your brain does.

Jonathan identified “capture” as central to my work. But I think what I’m really doing is trying to capture the uncapturable. Impermanence. Transformation. The moment when materials assert their own intelligence. The transcendental state when the maker disappears and something else emerges. The unpredictable timing of when a root will sprout from a ripe seed. I feel like this process is something that cant be forced, and happens spontaneously.

That’s why I’m stuck in contemplation. Because the work itself is about flux, about process, about things that refuse to be finished. How do you complete work that’s fundamentally about incompletion?

But Jonathan’s right, I need to capture these moments before they disappear into the swirl. I need to finish pieces so I can reflect on them. I need to trust my tacit knowledge. I need to work backwards from the revelations.

Like this one: sitting here editing beehive frames and suddenly understanding that the frame is the tension. The frame is what makes the organic variation visible. Without the frame, we wouldn’t see what escapes it. It’s really all right in front of our eyes- just waiting for that moment where we ‘see’ it.

Moving Forward

This conversation with my sister is the work. These observations about beehive frames, about solder temperature, about horizon lines, this is reflexive practice in real time. This is what Jonathan saw in my blog. This is what he’s asking me to keep doing.

I’m committing to finishing pieces. Not because they’re complete, nothing is ever complete, but because I need to mark moments in the cycle. The way our ancestors marked the turning seasons with celebration. It’s not about deadlines really, it’s about marking a moment in time that will pass and never come round again. To move from contemplation into action. To allow myself the vulnerability of resolution, even temporary resolution.

I’m committing to capturing light bulb moments before they disappear. Like this blog post. Like the nursing models. Like the beehive frame observation. These are the building blocks of a cohesive practice.

And I’m committing to trusting that transcendental state, the one my sister described, the one I experience when making my best work. The state where tacit knowledge takes over. Where the maker disappears. Where collaboration with materials replaces force.

Maybe I’m exactly where I need to be: in the space between the frame and what escapes it. In the collaboration between control and variation. In the moment when the solder reaches perfect temperature to flow it changes form into liquid. Molten, glowing; holding new invisible bonds between materials as it cools.

Maybe that’s capture?

References

DiClemente, C. C. & Prochaska, J. O. (1982). Self-change and therapy change of smoking behavior: A comparison of processes of change of cessation and maintenance. Addictive Behaviors, 7, 133-142.

Polanyi, M. (1958). Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy. London: Routledge.

Polanyi, M. (1966). The Tacit Dimension. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Prochaska, J. O. & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 390-395.

Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C. & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist, 47(9), 1102-1114.

Prochaska, J. O. & Velicer, W. F. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12(1), 38-48.

Rice, A. M. (Various works on communication in nursing, palliative care, and specialist nursing practice). Honorary Senior Research Fellow, School of Medicine, Dentistry & Nursing, University of Glasgow. (She was my university lecturer & her work on communication in nursing contexts informs this reflection.)

Rachel Emberton

MA Fine Art Practice, UAL

November 2025